Origins of Addiction: The Noble Nematode

Being retired means more time to read, and this spring I read “A Brief History of Intelligence” by Max Bennett. I can honestly say that it is my favorite non-fiction book ever; I can’t wait to read it again. Max weaves a remarkably elegant narrative (although at times quite dense) about how our brains evolved to become what they are today. While at the end of the story the human mind is, of course, the dramatic climax, that is not what caught my interest. Instead, it was the early evolution of the simplest forms of nervous systems before there were brains that sparked my imagination.

We understand today that there are lots of reasons why substance use disorders are increasingly common. Access is easier than ever, life is stressful and we all look for ways to regulate, some are predisposed to anxiety or have experienced physical and emotional trauma and are just trying to cope. The list is long, our environment, minds, and bodies are full of traps, and at times it seems more appropriate to wonder: do any of us not use something?

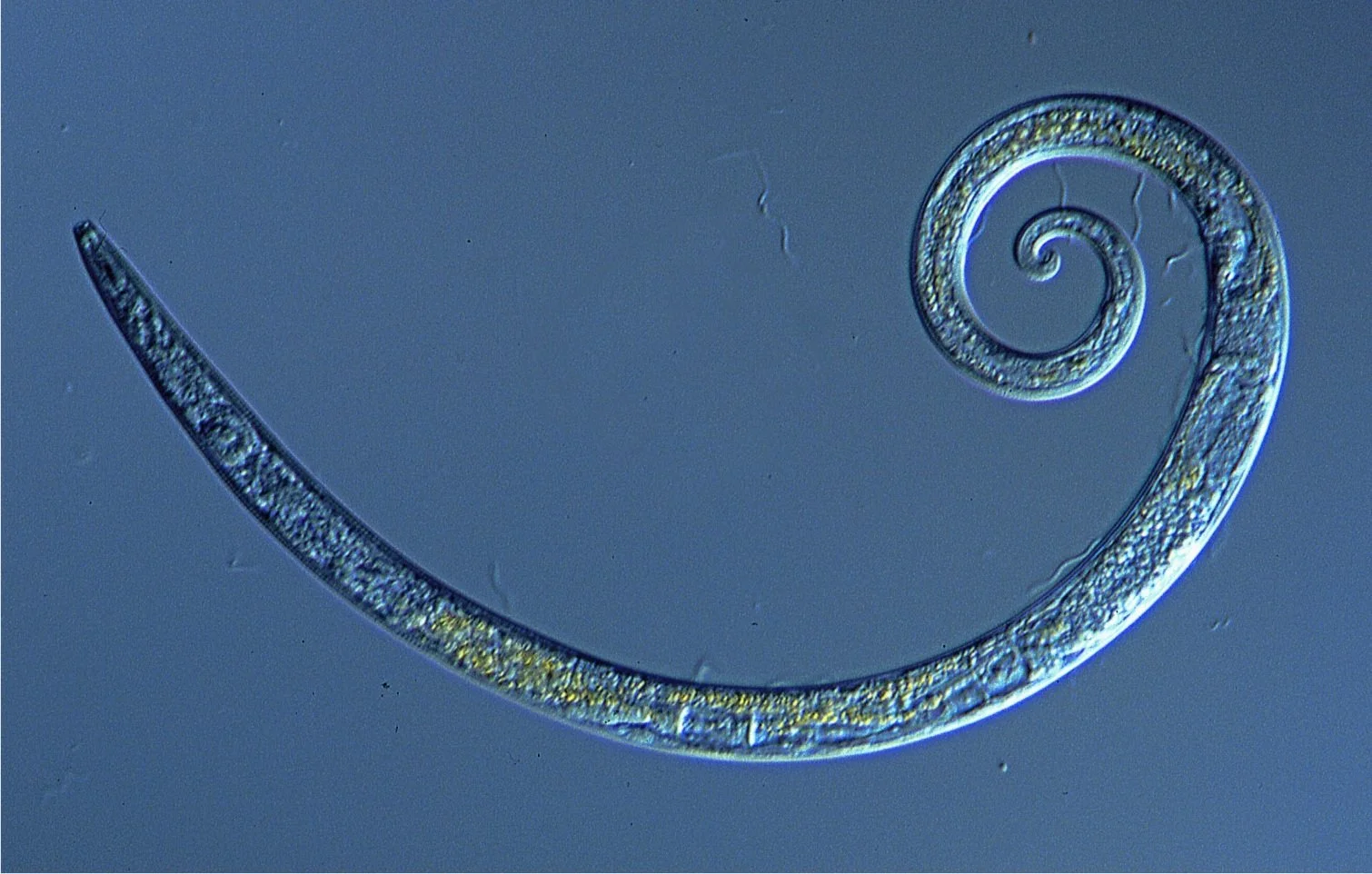

Enter the nematode: this tiny living fossil doesn’t even have a brain; in fact, its entire nervous system is made up of 302 neurons spread throughout its body and along a spinal cord. Some of these neurons are used to sense their environment, and together they allow the nematode to accomplish the first form of intelligence needed in animals - the ability to move and to steer towards food.

Why was something so primitive so interesting to me?

Because nematodes are addicts, too.

Humans are remarkably complex, so much so that it is almost impossible to understand cause and effect in our minds and bodies. If we want to understand why some people bend and others break, then we have so many variables to manage that it seems impossible. However, if you can study the processes involved in a simple animal like a nematode, then we should also be able to understand what happens and whether these mechanisms are also a part of how our more complex nervous systems work. Armed with that new knowledge, perhaps we can develop new treatments.

There is something else noble about a nematode with substance use disorder: no one would accuse them of having a moral lapse or character failure, nor a lack of willpower or mental illness - as I said, they don’t even have a brain. They don’t “choose” to do anything except to try to survive. This behavior is simply a product of their environment, biology, conditioning in their body chemistry, and neural adaptation that tips their “affective valence” towards substance seeking. Nematodes also experience their form of withdrawal when the substance is removed and behave differently until time allows them to recover and return to the normal or “naive” state.

What if we could understand what changes in a nematode’s body chemistry and neural pathways occur during the onset of addiction? What if we could understand the source of withdrawal symptoms and relieve them? Would that not only ease the difficult first 30 days, but even make it less likely that someone will relapse? Could we prevent cravings? What if abstinence were not the only way to “cure” substance use disorder?

Inquiring minds want to know.